Muslim Maritime Bloc to Control Straits

Strait of Hormuz

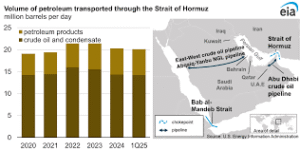

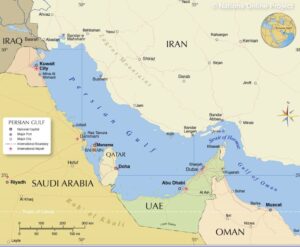

The shipping lanes in the Strait of Hormuz are located primarily in Omani territorial waters and partially in Iranian territorial waters and governed by international maritime law and the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). Iran’s naval presence has the ability to exert a significant amount of control over the strait however international forces, including the US Navy Fifth Fleet stationed in Bahrain can intervene to guarantee safe passage. In 2024 oil flow through the strait averaged 20 million barrels per day (b/d), or the equivalent of about 20% of global petroleum liquid fuel consumption. Attacks on merchant vessels in the Red Sea occur with increasing frequency and no Muslim rescue agency , under a unified civilian structure , exists to assist seafarers floundering in the territorial waters of Muslim Nation States after sinking of ships. On several occasions search and rescue operations have been conducted by contractors engaged by shipping lines .

Alternative Oil Routes to Strait

Alternative Oil Routes are present in Saudi Arabia and the UAE and oil infrastructure is in place that can bypass the Strait of Hormuz to mitigate any transit disruptions through the strait. The oil pipelines do not typically operate at full capacity and it is estimated that about 2.6 million b/d of capacity from the Saudi and UAE pipelines could be available to bypass the Strait of Hormuz in the event of a supply disruption.

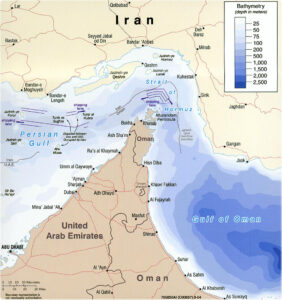

Strait of Hormuz Navigational Depth

The Strait of Hormuz is a narrow channel, approximately 30 miles wide at the narrowest point, between the Omani Musandam Peninsula and Iran. The Persian Gulf covers around 93,000 square miles or 2,51,000 square kilometres. It measures 615 miles or 990 km lengthwise and is 340 km to 55 km broad. The Strait of Hormuz connects the Persian Gulf to the Gulf of Oman. The Strait is deep and relatively free of maritime hazards with an average depth of 35 m. Its depth is greatest near the Musandam Peninsula and tapers north towards the Iranian shore. Generally, commercial traffic through the Strait flows through the designated Traffic Separation Scheme (TSS) north of the Musandam Peninsula but the water is deep enough for large ships to travel through an Inshore Traffic Zone south of the Omani island of Didimar. Depths in this area reach over 650 feet, but the Omani government restricts access to this area to smaller vessels in normal and peacetime situations. Prior to 1979 the Inshore Traffic Zone served as the main shipping channel through the Strait. Fully laden VLCCs can safely navigate through most of the Strait .

Credit;EIA

Credit;EIA

International Court of Justice

Historically, international maritime trade has developed through the use of the shortest navigable route between ports. This involved passing through straits being a natural and narrower route between two parts of the sea. The International Court of Justice (ICJ) in its verdict in 1949 in the case of the Corfu Channel (United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland v People’s Republic of Albania), recognised the customary value under international law of the right of all ships to innocent passage through ‘international straits’, specifying that these should be understood as those straits not only abstractly suitable for international navigation, but in respect of which there existed a long standing practice of use by a significant number of ships. The 1958 Geneva Convention on the Territorial Sea and the Contiguous Zone (1958 Geneva Convention) dedicated only paragraph 4 of Article 16 to the innocent passage through straits, stipulating that such passage in straits ‘which are used for international navigation between one part of the high seas with another part of the high seas or the territorial sea of a foreign State’ could not be suspended by the coastal State. Compared to the 1949 ICJ ruling, the rule was explicitly extended to straits connecting the high sea with territorial waters.

In the last decades the general extension of territorial waters up to the twelve-mile limit produced a considerable multiplication in the number of straits within the territorial sea of coastal States. The complete submission to coastal sovereignty of about two thirds of the international straits was clearly leading to a progressive restriction of the areas subject to full freedom of navigation, which was replaced by the more limited right of innocent passage , which in turn led to the reconsideration of the matter at the Third Codification Conference on the Law of the Sea. The Part III of the UNCLOS is specifically devoted to straits, with a clear intention to differentiate its discipline from Part II, devoted to the territorial sea. The regime of Part III is therefore a compromise solution, since the new ‘transit passage’ regime, which is much more favourable to States using straits than the non-suspendable innocent passage (downgraded to a rule valid for straits of minor importance), can be considered as a ‘compensation’ wrested by maritime powers in exchange for accepting the 12 mile rule as the measure of maximum territorial sea extent.

Credit;Maritime Education

Credit;Maritime Education

The issues arises that how is transit passage distinct from simple innocent passage. Unlike the latter, transit passage also extends to overflight, and does not expressly require submarines to transit on the surface therefore, there are fewer possibilities for the coastal State to limit navigation. This explains the resistance shown by many coastal States to the transit passage regime both during the Third United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea and after the entry into force of UNCLOS. In Europe Spain opposed the inclusion of the Strait of Gibraltar to this regime.So did Russia with regard to the straits in the Arctic Ocean despite its policy of supporting the widest possible freedom of navigation and also despite the Soviet Union being an ardent supporter of this new regime at the time of the Third United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea.

According to Article 37 UNCLOS, the transit passage regime applies ‘to straits used for international navigation between one part of the high seas or Exclusive Economic Zone and another part of the high seas or Exclusive Economic Zone’. To other straits, in particular those which connect the high seas or the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) with the territorial sea of another State, the regime of innocent passage which cannot be suspended shall apply. However, Article 38 provides for an exception to the regime of transit passage in the case of straits which, although connecting two parts of the high seas and/or the EEZ, are formed by an island belonging to a coastal State and its mainland and ‘if there exists seaward of the island a route of similar convenience with respect to navigational and hydrographical characteristics’. This exception is known as the ‘Messina clause’, because at the time of the Third Conference on the Law of the Sea the Italian delegation supported it in order to take the Strait of Messina out of the limits set by the coastal State for cases of transit passage. Yet a view expressed by those who doubt that the alternative route being the circumnavigation of Sicily, is always ‘of similar convenience’, does not seem to be entirely groundless.

Also Part III does not apply ‘to the legal regime in straits in which passage is regulated in whole or in part by long-standing international conventions in force specifically relating to such straits’ (Article 35). It is therefore without prejudice to what is specifically contained in treaties that refer to certain straits. The issue of interpretation of the term ‘long-standing’ persists and what is the ‘critical date’ which is not easy to determine. It is however, clear that the provision refers to international conventions in a technical sense, such as the Montreux Convention of 1936 on the ‘Turkish Straits’ and not to communiqués and joint declarations of coastal States. In contempraray times these agreements are depicting obsolescence especially in the light of new environmental sensitivities , climate change alerts and renewable energy powered fleets , since the very liberal regime thereby envisaged, with regard to night-time passage, no longer seems justifiable given the large number of ships in transit with potentially hazardous cargo.

Simple Navigation

As far as the obligations of the flag States of ships crossing straits are concerned, it is clear that the ships in question must refrain from any activity other than simple navigation, and that this must take place continuously and expeditiously. Coastal States, for their part, have the right/duty to regulate transit, both to protect their legitimate interests and to ensure the safe passage of ships through straits. To this end, they may indicate the corridors of traffic and prescribe the necessary traffic separation schemes. Whether they can also make transit subject to prior notification or authorisation remains a sensitive issue deliberated upon during the Third UNCLOS particularly with regard to warships. Many coastal States insisted, even at the time of signature or ratification of UNCLOS, on depositing interpretative declarations on the point, not only with regard to straits but also simply to the territorial sea, implying the offensive character inherent in warships regardless of any activity. The final text of UNCLOS, however, implicitly recognises warships as equal to merchant ships for the purpose of transit, as it does not contain any specific provision on the passage of warships.

Beyond the regulations adopted, and looking only at what takes place practically the common fact that emerges from the controversies sometimes referred to as proof of the legitimacy of consent for the passage of warships is that in these cases the coastal State’s protests regarding the unauthorised transit of warships are part of a wider dispute. In such dispute, the main issue is not the question of consent for passage but, as the case may be, the fact that the ships in question did not limit their activities to mere transit, divergences as to the regime of the waters through which they passed as well as general political and diplomatic tensions. Generally passage is granted to foreign warships also by States which at the Third Conference, and in their domestic regulations, maintain the necessity of the requirement of prior authorisation or notification. One could not otherwise explain the absence of any dispute concerning the issue of mere unauthorised passage.

Regulate Transit for Protection of Marine Environment

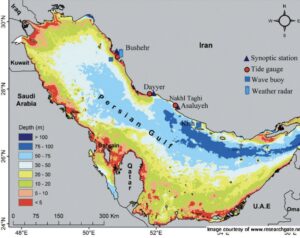

The most recent practice depicts an increasing tendency for coastal States to regulate transit for the protection of the marine environment in the general interest of the international community, including through bans or notification requirements. This is manifested in adoption of mandatory pilotage systems for certain categories of ships to prevent the risk of accidents and is widespread as mentioned in the ‘user manual’ for Messina Strait. The issue here is different from the transit of warships, because of a general interest in environmental protection, which is certainly not attributable only to coastal States. International obligations and prohibitions which may appear prima facie unjustifiable from a legal point of view because they are incompatible with the rule that passage in straits cannot be suspended, but which are reasonable in the light of the lack of appropriate provisions for the protection of the marine environment in such areas. Mangroves in the Gulf waters require a certain tidal flow and a perfect blend of fresh and saltwater for growing as they maintain a unique aquatic ecosystem and act as breeding and nesting grounds for different kinds of fish, insects, birds and crabs and breeding shrimp and other fish species. Mangroves are found along Hormozgan, Boushehr and Sistan. Creation of Qatar , Doha’s Pearl islands has damaged the mangroves and the marine ecosystem. The Pearl-Qatar is one of the largest estate developments in the Middle East perched on 4 million m2 of reclaimed land and located 350 meters offshore of Doha and has created over 32 km of new coastline for use as a residential estate with an expected 25,000 dwellings and 50,000 residents by the end of 2021.

Collisions Spills Pollution

Over centuries the straits regime has been conditioned by political and military issues. The solution provided by UNCLOS to navigation in the straits has also seen strategic and military interests in maintaining important maritime routes open to navigation prevail over the interest in preserving and protecting the marine environment. Environmental concerns should be given due weightage when assessing applicable regimes . Straits are termed watercourses which by definition are limited in size but frequently used. The risk of accidents such as collisions or spills of polluting material and routine dumping of cruise ship waste is higher than in open spaces. Transit is often made difficult due to geographical and hydrographical characteristics. The effects of pollution caused by accidents can be devastating, especially in the case of ships such as oil tankers, nuclear-powered ships and ships carrying hazardous or noxious substances. It follows that, despite the interest of the States using them, the protection of the marine environment in straits must be considered as the essential concern. The sharp bend in the strait at the Musandem Peninsula, where the shallow inflow from the Gulf of Oman is forced to turn more than 90 degrees as it enters the Persian Gulf, could possibly lead to such a recirculation in the lee of the Peninsula with positive impact on marine life.

Straits’ Navigation Regime

Warships and Merchant Vessels

The straits’ navigation regime as provided for in the UNCLOS is therefore compulsory for States which have ratified the Convention and distinguishes the right of passage which cannot be suspended from transit passage which is more favourable for vessels in navigation and is applicable to straits ‘used for international navigation’.This expression, in accordance with international case law, is to be interpreted restrictively, in the sense of excluding straits which are only ‘potentially suitable’ for international navigation yet not currently used.

Exception to “Not in My Backyard “Rule

According to international practice, this rule is to be interpreted as not diversifying the regime for warships from the regime for merchant ships, since it is the activities and not the intrinsic nature of the ship that may constitute a threat to the coastal State and consequently make transit offensive and therefore unlawful. The exception to the rule just mentioned concerns the passage of ships potentially dangerous to the environment, because of the cargo carried or the propulsion mechanisms used and in the general interest of the international community, it is reasonable that the coastal State may require notification of the passage of such ships or more restrictive conditions for such passage, even to the point of prohibiting transit of particular categories of ships or in particular circumstances.

Iranian Role in Management of Strait of Hormuz

Credit;Maritime Education

Iran has traditionally construed the management of the Strait of Hormuz as a strategic weapon in international politics even as early as the codification of Geneva Convention ,where Iran voted against the right of innocent passage through international straits, signing but never ratifying the 1958 Geneva Convention. In the year 1959 ignoring howls of protests from the United Kingdom and other States it proceeded to extend its territorial sea to twelve miles, with reference to the Strait of Hormuz, citing security reasons as motivation. Iran is not even a Contracting Party to UNCLOS. Iran even after the extension of its territorial waters to twelve miles, claims the application of the regime of non-suspendable right of innocent passage in the Strait of Hormuz, rather than transit passage, with the burden for warships of the need to obtain prior authorisation for passage. Iran and Oman opposed this new discipline from the first moment, as did other coastal states of important straits including Turkey and Venezuela which like Iran, did not ratify UNCLOS. Other States like Spain and Russia have ratified UNCLOS yet find it difficult to recognise the validity of this institution with respect to the straits under their sovereignty, in many cases maintaining in force laws adopted prior to the ratification of UNCLOS, which in fact deny the right of transit (in accordance with the ‘not in my backyard’ rule) .

UNCLOS Ratification and USA

It is paradoxical that the most strenuous defender of the customary value of the right of transit established by UNCLOS is USA which has not ratified the Convention and is a party to the 1958 Geneva Convention , which does not provide for this right . The official position of the US Government, long been supported, in particular through the FON (1979 Freedom of Navigation Program), is :

(a) Iran may control the passage through the Strait of Hormuz but may not close or block it, and as a signatory of UNCLOS, may not act contrary to the purposes and object of that Convention, in light of the rules of treaty law codified by the 1969 Vienna Convention.

(b) The right of transit passage is also provided for by customary law, since it reflects an established practice and corresponds to the opinio iuris of the majority of States. The possible closure of the Strait, the prohibition of overflight and the obligation for submarines to transit in emergence would therefore always be unjustified and illegitimate, since it is contrary to the right of transit passage as provided by customary law as codified by UNCLOS.

Muslim Maritime Bloc to Regulate Navigational Passage through Strait

The Persian Gulf is bounded by Muslim Maritime nations and many are significant hydrocarbon players . In the Arabian Sea region , Gulf of Persia and Gulf of Oman many Muslim Maritime countries are either producers or consumers of oil and gas and maintaining the oil supply chain is critical for advancing of Muslim strategic, commercial and financial interests . The Organisation of Islamic Conference (OIC) can play an effective role in harmonising and integrating multi modal supply chain sustainability , versatility , innovation in exploiting the commercial maritime potential and digital enhancement in this vital waterway bordering many Muslim States coastlines. Commercial unity amongst Muslim Maritime nations is the need of the hour and the recent spate of hostilities in the Persian Gulf region has sounded the clarion call for commercial unity and logistic maritime integration. The maritime traffic in the Gulf is increasing and existing cargo and container handling capacity of ports is being enhanced. The Strait of Hormuz width and depth varies and it will soon have to be dredged and navigational passage and hazardous cargo handling be carried out through digital and satellite remote tracking in order to prevent collisions. The Muslim coastal states in the Gulf region should establish a common and coordinated digitally driven traffic and logistic corridor management system on a revolving basis . Slower movements of tides and currents in the Persian Gulf requires more sensitivity towards oil slicks, coastal sewage and industrial effluence dumping , reclamation and coastal development to extend coastal limits , marine ecosystems , religious tourism , pleasure tourism , multi modal logistics connectivity, seafarers capacity building , digital and artificial intelligence (AI) cargo and container handling , Ship to Ship (STS) regulatory controls, introduction of International Hydrographic Organisation S-100 Navigation geospatial data standards , island sovereignty dispute resolution mechanism besides other matters .

Kingdom of Saudi Arabia vying for Muslim Maritime Bloc

Credit;SeaNav Marine

Credit;SeaNav Marine

The Saudi Ports Authority (Mawani) and the National Petroleum & Petrochemical Tank & Pipelines Company (Petrotank) are developing an integrated ship refuelling centre at King Fahad Industrial Port in Yanbu on a 110, 700 m2 site involving an investment of almost USD $ 133 million spread over the next two decades. A merchant ship consumes around 40 metric tonnes (40,000 litres) of heavy fuel in 24 hours , during its voyage and many ports vie to become bunkering hubs . The Saudi Ports Authority is aiming to enhance the competitiveness of Saudi Arabian ports by developing fuel and oil infrastructure essential for delivering state of the art logistical services, offering fuel storage and bunkering services to attract ships , diversification of Saudi hydrocarbon industry, handling of increased ship traffic, and strengthening regional and global port competitiveness. The National Transport and Logistics Strategy envisages an investment of around USD $ 266 billion by the end of this decade to establish Saudi Arabia as a major logistics hub in the world.

Author ; Nadir Mumtaz

Trademark Blue Economy IPO-PK

Credit ;

http://DOI: 10.1029/2003JC001881

https://doi.org/10.1029/2003JC002145

https://www.qil-qdi.org/the-strait-of-hormuz/

https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=65504

https://www.britannica.com/question/Who-controls-the-Strait-of-Hormuz

https://www.strausscenter.org/strait-of-hormuz-geography/

https://www.marineinsight.com/know-more/persian-gulf-facts/

Leave A Comment